Extended Research

After my initial visits to the Drawing Room in Unit 1, I felt the extended research was an exciting chance to partake in informative research and began thinking about all the different ways I might go about it. Some of the many directions I travelled on my research journey included: researching rubbings at the British museum; I thought about archeology collections and archives that housed rubbings; I thought about how my original degree in classics might be helpful in approaching material collections such as ancient mosaics or other historically important sites; I considered historic sites and features such as the steps of the Bodleian library at oxford university; I attempted to research about the possibility of accessing abandoned buildings and even looked into haunted spaces in London that might have some significance. All these ideas are exciting and perhaps are worth further consideration.

Allegra Pesenti Interview

My first breakthrough with an external partner was to contact Allegra Pesenti, who agreed to a written interview. I managed to get her email after contacting the Hammer Museum, where she used to work. Pesenti was the curator of the exhibition and subsequent publication “Apparitions: Frottages and Rubbings from 1860 to Now, Feb 7–May 31, 2015”. This text was important for my research, and I had many questions since reading it. The interview went as follows:

Tom Harper:

In a time when touch is so transgressive, how relevant is bringing back a sense of touch and connection in the world through art?

Allegra Pesenti:

I think a sense of touch and connection are forever vital to art, and of course it is all the more relevant at the heels of the pandemic in which we have been physically distanced from both human and material ‘closeness’.

Tom Harper:

I’m interested in how you came to select the artists that you did and the works that you showed. Perhaps you could talk a little bit more about what drew you to these artists and works?

Allegra Pesenti:

Artists immersed in the practice of rubbing and related work appeared in my path as soon as I started thinking about the subject both historically and in the present. A revelatory moment was Jennifer Bornstein’s exhibition at Gavin Brown’s in New York city, in which she rubbed the entire surface of the floors of the gallery and placed the sheets of paper on the walls, creating a monumental reversal of space and sense of disorientation. I was also struck by how the marks of the floors emphasized the site’s age and history, as if she were retrieving its ghosts from its inner linings. Bornstein’s rubbing practice evolved from abstraction to figuration and remained a main point of inspiration throughout my research on the subject.

Tom Harper:

You write about traces in the exhibition and how recording objects, surfaces or places can reveal and assume a new presence as rubbings. I am very interested in rubbing to reveal void spaces such as cracks, scores or the tiniest marks of wear and tear. Perhaps you could tell me more about frottage’s power to transcend its subject matter and create new meanings?

Allegra Pesenti:

There is an element of wonder and unexpectedness in rubbings which is what made the practice so appealing to Surrealist artists. Max Ernst found his deepest fantasies in the grains of the wood of his floorboards. A comb easily morphed into an animal’s body. I think that ability to ’transfigure’ objects and to see beyond their common forms and uses is at the core of this form of artistic expression.

Tom Harper:

Is there any way that you think rubbing and frottage has changed and developed as a contemporary art practice since the exhibition?

Allegra Pesenti:

Artists continue to experiment with rubbing and frottage and the practice continues to stretch into new territories - whether sensory, physical, or performative. The Jazz musician and composer Jason Moran traces the taps of his keyboard onto paper and creates some of the most poignant and deeply moving ‘recordings’ of his sounds and improvisations.

Tom Harper:

And what is it about rubbing that draws artists time and time again to use this most basic and ancient of drawing methods; What is it about this process that keeps it relevant in contemporary art and in particular drawing?

Allegra Pesenti:

Perhaps the very fact that it is so basic and accessible, yet also deeply layered and complex in its possibilities.

Tom Harper: Since Apparitions, frottage and rubbings are being used as the mainstay of artists like Ingrid Calame and strongly featuring in the work of high-profile artists such as Kiki Smith and Catherine Anyango Grünewald. Have any artists stood out for you since the exhibition that you think are important and that you would have included in the exhibition if it had been put on today?

Allegra Pesenti:

As I mention above, Jason Moran for sure. I love the work of Kiki Smith and would certainly include her if I were to do a take two of this exhibition. There are so many artists I would have loved to include but couldn’t for reasons of space and accessibility…so I’ll save that list for the next iteration!

Raquel Serrano Interview

Raquel Serrano is a fine art doctorate student at the university of seville. She was awarded a fellowship in print at Camberwell College of Art in the spring term of 2022. She uses rubbings and frottage and plans to continue to do so as part of her research. I asked her if she was willing to do a short, informal interview and she most gratifyingly agreed.

Here is what transpired:

Tom Harper:

-

What is it about frottage that excites you and how did you come to see this as an important part of your practice?

Raquel Serrano:

I became interested in frottage from my PhD supervisor María del Mar Bernal who wrote a great article on the subject. (https://tecnicasdegrabado.es/2020/el-frottage-todo-esta-en-el-roce). I am interested in experimentation with the printed image and how printing can turn into drawing. The images produced by say rubbings replaces the reality of what was there. I want to question what the reality of an image is. I like how rubbings can look like quite abstract images but are in fact highly representational. So, the image is the surface, but the surface is moved from its original place. I’m playing with our concept of an image and the concept of perception.

Tom Harper:

-

What new materials are you using to make your rubbings and why?

Raquel Serrano:

I have been working with canvas recently and I have found it can be very pragmatic in a lot of situations, especially when you are outside and rubbing on the ground. Before I was working with large sheets of paper, using a sponge and graphite powder to apply the rubbing. I have found that, unlike paper, fabrics like canvas are both more durable, and much more pragmatic when you are outside. They will not ruin if they get wet and they can even be machine washed if you apply fixating beforehand. They do not weigh much so they can easily be transported, and it allows you to work in large formats since it is difficult to find paper rolls of that magnitude. I also found that you can add eyelets and can easily be stretched out in a space like a painting. This makes them very pragmatic for very large rubbings in a way that paper just doesn’t easily allow for, especially when thinking about hanging them in a space. They also have a more haptic element to them; in that they can become quite sculptural. You can fold, crumple and manipulate them in many ways.

Raquel, Serrano, Transfer the surface, Frottage graphite on canvas, 100 x 375 cm 2022

Tom Harper:

-

What artists have you researched and what is it about their work that you find fascinating?

Raquel Serrano:

I am interested in the works of Juan Carlos Bracho who has rubbed the walls of a gallery space with graphite. By drawing directly onto the walls in this way, he creates beautiful ephemeral drawings, that get erased from the space after the exhibition ends. I am interested in the imprintment of the land itself and have appreciation for the work of Andrea Gregson, who takes large scale rubbings of rock formations. All these artists reflect on the space itself, moving the surfaces, manipulating them, folding them and turning the images of reality into three-dimensional elements, which invite the viewer to inhabit the image

This interview was great for considering my methods and new choices of materials and the artists who use them. I experimented with using canvas for rubbings as I may wish to use it in the future if I go outside or for works that need to be hardier and need to be on the floor or manipulated in some way. (see process and critical reflection).

Taking rubbings at the Type Archive

After doing some research to see where I might find some historic printing machinery to further my research, I came across The Type Archive, which housed an assemblage of historic printing presses. I spoke with the curator, Sallie Morris, and to my delight I was given not only a tour of the archive but also allowed to take some rubbings of the machinery.

The archive has some truly amazing artifacts from the past and it was fascinating to delve deeper into the history of print. I settled on the Wharfdale-style machine called the “Defiance”, which was made in Yorkshire by inventor David Payne back in the 1860’s. This machine revolutionised the printing trade and it was an incredible honour and with great excitement that I undertook the task of producing a print of the press that had created perhaps millions of prints itself. The extra weight of historical importance of the machine was something I had never been able to engage with before with a space or object and it really added to the interest and significance of the work for me.

|  |  |

|---|

Rubbing the Wharfdale not only helped me further develop my visual language but also formed a greater emotional connection with these archaic, increasingly rare artifacts. This feeling was only enhanced by the knowledge that the archive was losing its funding and would no longer be open to visitors. The very machine I was rubbing would soon be stored away somewhere indefinitely, behind closed doors. I came closer to understanding why these machines have emotional significance and importance. The arts and culture are under increasing threat and these prints could perhaps be a way of showing what we are losing as a society.

The experience of this enigmatic space and its relics, dripping with the history and the importance of Britain’s cultural and technological heritage makes me keen for further opportunities. There are other institutions that I could attempt to contact based on connections I have made with the curator there. I feel trying to approach collections, archives and institutions of this sort could be an important part of my practice in the future.

White Chapel Gallery

I have been interested in what it is about the studio and creative spaces that fascinate me and why they are worth commemorating through my interventions. I wished to contextualise my understanding of the wider debate surrounding the studio in contemporary art practice and so after doing some research I went to Whitechapel Gallery to gain further insight. I was most fortunate that it was having an exhibition that touched on this issue. The exhibition itself, A century of the artist’s studio 1920-2020 was very illuminating, concerning itself with the notion of the studio space, both as a public space to showcase the artists identity or as a private space to "take refuge, reflect, experiment and even cannibalise the studio itself." (see contexts to read more about how this important exhibition helped my practice).

TOM HARPER

PROCESS AND CRITICAL REFLECTION

In a similiar vein to Unit 1 and 2, my practice continues to delve deeper into the exploration of surfaces and objects through rubbing and imprinting techniques. I have expanded my practice both in terms of complexity and scale, finding new objects and surfaces that continue to question how we perceive the world around us. New methods and thematic concerns have come to the fore, all the while the expanded field of drawing, the role of touch, the studio and the creative process itself remains central to my practice. Print making and drawing interventions, now also including further exploration of architectural space, come together to build communal drawings from the traces of human activity: all conferring a personal haptic embodied experience of discovery, to the outside world.

PRINT ROOM AND THE PRINTING PRESS CONTINUED

Print Room Rubbings, both Finished Works and Sketches

Documentation

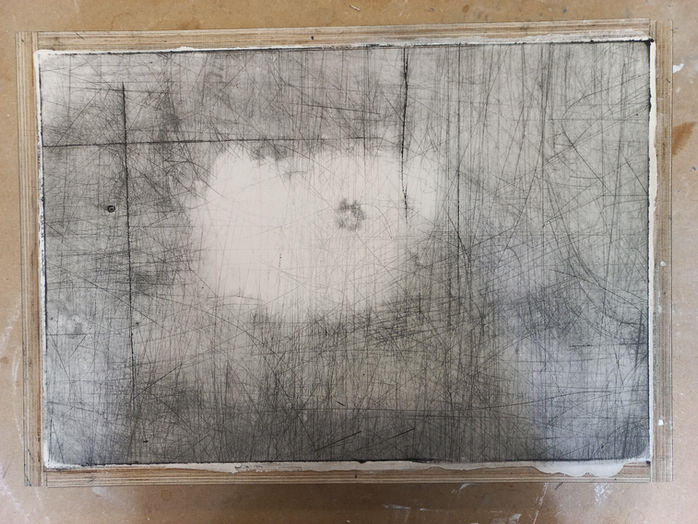

When I finally found a space large enough to document the rubbings for the intaglio printing presses and the other rubbings of machinery in the print room, it gave me some new perspectives on the undertaking. I was influenced at this stage in how I arranged the presentation by Simon Woolham, Washead Beshty (discussed in Unit 2 Contexts) and the book Understanding Installation Art (1991), by Mark Rosenthal. I had some trepidation about what the different elements of the deconstructed presses and various machine parts might look like until I saw them together for the first time. As I put them up on the wall, thinking organically about their synergy, one work to another and the overall presentation, I was happy to discover that different elements really spoke to each other, sometimes in rubbings that I was half expecting and hoping for and in others which were quite surprising.

The different wheels spoke of motion, an animated record of an industrial process. The large wheel and the smaller wheels on the left side, bisected in the middle by a further large circular cog, becoming descriptive thematically of this. The tools in the middle of the composition also had an animated appearance to them, as if you could feel their function, turning the pressure screws from various points of view at various moments in time. They had a rhythm that spoke an activity, linking the other tools in the middle by their placement. The different versions of the rubbings, in various stages of completion, were evocative of a manic process of printing, but also of decay and erosion. The rubbings are a fleeting trace, the marks of the passage of time. The half-finished wheels, tools and presses are indicative, in their now divorced state from their original contexts, as being like commemorative relics that speak of these printing machines once glorious past. This is only reinforced by the black and white colour that unifies them, the signifier of the past, like black and white photos or ghost-like apparitions. (The significance of monochrome in my work is something I want to study in more detail). It reminded me of Mike Nelson’s The Asset Strippers (2019), that showed the leftovers from Britain's industrial legacy, becoming an ephemeral remembrance of time, memory and the end of an era.

The deconstructed presses, when arranged on the wall, started to make sense in relation to each other and came alive. However, what was more surprising was that as I included more rubbings onto the wall, including initial sketches, sketches attempted with different media and other rubbings, such as the feet of the guillotine and even the Wharfdale press, the immersive window into this bizarre world took on further connotations. Rather than simply mapping out various separate parts, the assemblage combined to record a more personal experience of discovery.

Each facet of the machinery spoke of unique sensory journey. They act as a record of moments in time, imparting an experience of the movement of the hand and the mark of the pencil. It choreographs my feelings about the print room and its antiquated machinery, each sculptural carving into their surfaces, edges and borders, a sign of tentative curiosity about surfaces and trace led by an investigative hand. All that intensity and care, choice of surface, the minutiae of gestural flourishes, show the joy of being in that space, a love and devotion to the processes of printmaking via the medium of drawn print. This process is substantially enhanced by the sheer scale and breath of the etching artifacts on offer. It hopes to provoke a reaction of awe and stimulate interest in the experience I am trying to share with my audience.

The works produced a strong emotional response in me. I felt there was a sort of mad absurdity about putting up this enormous show of machine rubbings for essentially no one but myself and the camera in that given moment; it's like the work was just existing by itself. Perhaps this was what this project was all about, the culmination of all this labour, the first encounters, the earlytentative pieces, the long hours on larger works, was to just see these fascinating objects revealed to the world.

Cogs of Machinery, Modern Times (1936)

Later, I became aware of the film Modern Times (1936), and the scene in which Chaplin gets caught in the machinery resonated with me. I felt that I had also got sucked into a world of old gears, cogs and wheels, and that ironically as I was trying to give life to it, touching it, caressing it, getting deep into its vital organs the experience of discovering it through this most intimate of senses has touched me and brought forth all these emotions, ideas and experiences. Its uneven, yet smooth surface, its endlessly varying texture. Its strange shapes and boundaries, what lies beneath its surface that makes it what it is. It’s a unique space for me to find out about my interests in things in ways that are unique and as indexical as the thing being rubbed. This too could be what this work is about, that trying to understanding the world through touch allows for the manifestation and expression of feelings and connection that are difficult to easily articulate through other means. The process of rubbing has created such an intimate relationship with the printing presses and the broader print rom. I feel I have grown as it has grown, and I have become one with the machinery, it has become part of me and the work has taken an autobiographical turn, as I touch the world to become closer to it, I am myself touched.

Exhibition Meeting

The experience of curating my work for documentation was very rewarding and helped me to think about how I might present the work to a wider audience. I was aware that I did not have enough space as I might have wanted to present a complete view of my sensory encounters of the print room. Therefore, I began to think how best to present my work within a wider framework of a huge group show with a more limited scope. For the exhibition proposal, I contemplated about where things might exist within the space. I felt the works on paper had a lot of room for exploration in terms of where they might be placed, perhaps going on the floor (in a similar curatorial move to the Dialogues Show), or quite high up. I briefly toyed with the idea of placing the large slabs on the wall, hung with metal shelf onto a series of nails, but it quickly seemed to me right to show the casts, which after all were indexical to a work top that you would look down on from the floor, and this felt to me to be the most appropriate way for it to be seen.

After, submitting the Unit 2 platform, I was asked to think further about editing, refining and selecting completed outcomes. The artwork was very heavy, therefore we had a discussion whether it was feasible or not to have it in one large cast. I decided to scale back on my ambitions at this time and try to make work in smaller sections, for now focusing on making an A2 or A3 sized cast to compliment the smaller casts that have already been selected.

I was encouraged to further consider how to topographically relate the elements in the space, thinking in a scientific way like a museum curator. Sarah and Kate had some very good suggestions about working with shelving for the sculptural elements, Sarah also gave me the idea of working with bits of wood to raise the casts or the original surface as a readymade off the floor, creating a nice shadow. I produced some sketches, playing around with these concepts. (See Wilson’s Road Summer Show).

Mid-Section Gear Box of the Big Press wheel

Large Rochat Wheel, Mid-Section Gear Box

In preparation for the show, I continued to take rubbings of the large and small press in the print room. The midsection behind the wheel was a distinct challenge, the surface being so tightly wedged behind the wheel, that it was difficult and almost impossible in places to get any kind of solid contact with the pencil. On top of this, it took some painstaking measurements and calculations to even get it so that the circle was the exact size of the axle and fitted onto the press nicely. I made sure there was good room in the margins for the mechanism rubbing, as this would help it become a better composition. I was still being influenced by Toba Khedoori's expansive use of negative space.

Calculations, Measuring and Cutting the Cylindrical Shape in Bible Paper

Planning and diligent care was required to get the best out of it. To make matters worse, the press constantly leaked grease onto the paper with even the slightest movement of the wheel. I made sketches and rubbing plans of the area to be rubbed, which included rubbing on my knees, on my back prone on the floor as well using very small pencils and my left hand for difficult to reach areas. The performative elements of making these rubbings were still prescient in the work.

|

|---|

|

|---|

Paper Perfectly Fitting the Press; Rubbing Plan for Mid-Section

I made several versions of the rubbing to search for the best methods and quality for producing the imprint.

First Draft of Mid-Section

I was quite torn between the first rubbing, which seemed to have such a strong Bacon-like quality to it, seemingly akin to an apparition in a state of disintegration. I was still being influenced by the RA show ‘Francis Bacon, Man and Beast’ at this time. The distressed quality of the paper, combined with the grease that leaked around the circular opening, gave me the impression that this had anthropomorphic aspects, such as a mouth. The third version was a better rubbing overall in the sense it fully and completely captured the surface’s texture.

In retrospect it didn’t quite have the space around the edges that I wanted, and the grease from the machine from the first one seemed to provide an interesting quality to the work. It felt like you were touching the very heart, the blood of the machine. In the end I decided on the third rubbing as it felt more ‘complete’, and a cleaner version than the first. The texture was fuller, and it felt like a more resolved outcome. I am not sure whether this was the right decision, but it was a tough choice.

SUMMER RESIDENCY AT WILSON’S ROAD

Scaling Up the Ink Casts

At Wilsons Road, I was likewise also working on producing a larger cast of the print room work top surface for the Wilson’s Road exhibition. I removed the mid-section of the smaller casting rectangle that I had used to make the smaller casts previously and started to work on the larger surface itself for the first time.

|  |

|---|---|

|

Casting Tools: Casting Rectangle; Ink; Plaster Cast

The first result was hurried, and I did not use my hand to wipe the surface. I found that working on a larger scale with casts proved quite challenging compared with working with smaller sizes. I didn't quite mix it right and I put in too much plaster. This resulted in it hardening too quickly and the consistency created a different ink cast to the one that I was hoping for.

There were three main issues that were problematic for me in this piece: Firstly, I was unsatisfied with the white patch in the middle because it takes away from the marks that are there, leaving a desert of white. Secondly, the fact that the cast seemed fragile and was cracking in places was likewise a problem since working at larger scale would only make it more likely to crack and break. Thirdly, the cast was too dark for what I was looking for. Although the inverted image made the work perversely compelling, the moodiness of the cast was not enough to save it from being too dense and overpowering. It was clear working at scale was going to be more challenging than I had at first realised. The work did at least show the potential of working with a larger format, in places looking compelling and drawing the audience in.

The fragility of plaster was brought home to me at this time, illustrating the challenges working with plaster at a larger scale would impose.

Broken Ink Cast

On the next try, my relationship with this piece through manual contact, was crucial. I hand wiped the surface and this produced a much better ink consistency for the plaster to adhere to. It is apt that the act of hand wiping, this tactile, physical engagement with plates and surfaces as well as the ink medium, gives the plate tone its moodiness. It is through this process, led by the sense of touch, that my ability to manipulate the ink to capture more of the delicate drawn lines strongly relies. Wiping the plate of an etching by hand has always been more than a mechanical process for me. I was taught to really ‘feel’ the plate. Moving the ink around and over the surfaces and scored etched lines is gestural, almost like drawing with one’s hand. It feels almost spiritual to wipe a plate, to reveal the surface and get to a higher truth of expression. I think about the way that Rembrandt would wipe his plates and how there was a mystic element to it. He would literally reveal the story of Christ, as he sensitively pushed away just the right amount of ink with his hand to better capture the mood of the story he was trying to tell. For me, the process of wiping reveals the surface and the texture that’s been captured. I never had a vehicle that could do justice to this idea that has always fascinated me, that is revealing the process of making, what lies beneath the surface of things. This is like a palimpsest and an example of this would be the many states of rembrandt’s crucifixion etchings which reveals the manual process of making. Through my practice, I aim to explore what otherwise might be hidden, overlooked or neglected, in this way revealing a potentially interesting history. I’m therefore excited that this hand related method could provide such a means to explore this further.

Ink Cast Displayed at Wilson's Road

I was still not quite getting the surface I was hoping for. The large white mark in the middle of the cast was still present but it was a step in the right direction.

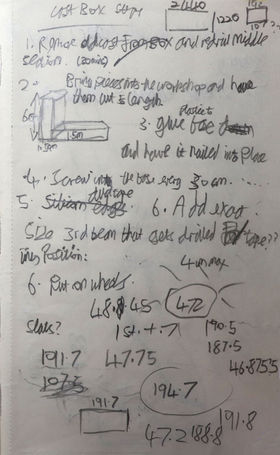

I then proceeded to build a platform which would allow the cast to be scaled up safely, having one eye on the show for Copeland gallery in November. In consultation with James Ireland, I drew up a set of simple diagrams and produced a plan for the platform’s construction.

|

|---|

|

|---|

Diagrams of the Casting Platform

The first step was to procure a large MDF board that would firmly support the worktop on top of it. I then sawed-off thin strips from the platform to act as a barrier to stop the plaster going over the sides. The strips running lengthwise measured 191.7 x 6 x 1.5 cm. The other strips running vertically measured 6 x 105 x 1.5 cm.

MDF Board Cut to Size

I then drilled and screwed in nails into the different thin strips so they formed a rectangle that could fit on top of the MDF board.

Rectangular Barrier Screwed in and Board

Next, I drilled in holes for the different sections in which the wooden strip would act as a divider and barrier for the four plaster cast sections.

Notes; Measuring and Rectangular Divider

After this, I used carpenter’s tape in the middle of the MDF board to firmly stick down the worktop.

MDF Board Stuck Down with Carpenters Tape; Finished Casting Framework

I then carefully measured where the holes would go on the sides of the MDF board and drilled them every 30 cm from below. I then attached the MDF board to the wooden strips. Finally, I then attached the wheels using a small piece of wood to buttress against the side of the platform.

Wheels and Carpenter's Marking Gauge for Individual Scew Aligment

At this time, I found out the reason why my casts were not coming out how I was expecting. Plastic sweats when one cast's plaster from it - the temperature and sweating increasing the more volume that is used. This means that water builds up and can create the white spots that were seen in earlier works. This led me to a few conclusions. Firstly the thicker the plaster the less the plastic sweats and so a fine balance is required to get the right consistency and ink details. Secondly, since jesmonite is placed on much more thickly and is thinner material, it would be well worth experimenting with polymer-based plaster as an alternative means of meeting my objectives. The platform allowed me to not only cast the table top safely into four sections, but it also allowed me to deal with the whitening issue as well.

Three Casting Platforms, Including Finished Large Platform

Inky Coverings

I also began keeping paper hand covers made from tissue and ordinary copier paper that I was using to avoid getting inky hand smudges on the larger worktop surface. I was still thinking about Noble’s ‘Dirty Books’, the collection of all his old and used foolscap papers for guarding his drawing. I was interested in doing something similar, finding value in the traces and remnants of wiping. The imprints of inky fingers on the paper surfaces act as a kind of recording of the process of wiping the surface. It captures the history of the embodied movement of discovery through touch.

Inky Imprints

I feel that it helps further outline my interest in the studio and practice, the left-over material traces of making and process. These smudges inevitably take on autobiographical connotations, however I am more interested in them as a new lexicon of embodied drawing through touch. Leonard Diepeveen, in Shiny Things (2021), describes smudges thus:

“even the calligraphy of smudges is unique: a hurried, aggressive smudge differs from a smudge that is the result of a contemplative touch or a caress. One reads a smudge’s history; one notices its duration, reading its implied pressure, speed of application, and direction as meaningful. Even a smudge’s positioning on an object refers to a body” (Diepeveen & Laar, 2021., p.83).

I feel this is quite a fascinating idea that something as abject and incidental as a smudge could have all this life and energy. The exploration of rubbing, polishing with ink, can leave these material artifacts that speak to this embodied process. I have been looking at various artworks that have looked at imprinting the body, especially the hands. The “panel of hands” found in the El Castillo cave in Spain is an interesting example of recording imprints, that shows the primal nature of tactility and recording. I am researching into the work of Yves Klein's “anthropometries” and Antony Gormley’s soft ground body etchings, which I wish to research further.

El Castillo, 'The Cave of Hands', Spain.

I am aware of the various aspects of fingerprinted smudges such as the auratic quality that smudges are a signifier for (Walter Benjamin), as well as the “ephemerality and fragility"; an absence that is now memorialized in print. My work does have certain connotations of loss. It questions what is left behind and tries to capture what is lost. It talks about decay and what we all may have ignored as we head into the digital age. I am interested in exploring this idea of loss and absence further. I plan to progress with these images by perhaps turning them into etchings and then into a book, recording the gestures of making.

References

Diepeveen, L., & Laar, T. v. (2021). Shiny Things. Intellect Books Ltd.

Cracks

At this point I began the installation for the exhibition at Wilsons Road which you can read about here. I also began working on a series of rubbings in the abandoned old studio that further investigated other cracks on the studio wall. These cracks were a continuation of the large crack work I had already made in Unit 2, rubbing down and to the side of the larger crack as it seemed to grow and splinter off the studio wall in many directions. The idea was to expand on the scale of the previous work and make a larger, and more ambitious immersive experience.

|

|---|

Making of Cracks

|

|---|

The Cracks Grow

It was like a journey of discovery, but done blindly, feeling and fumbling my way across the surface of the paper, excavating just beneath the surface, never sure what I was going to find. It is still quite amazing to me that something as humble as a crack, a space that many would consider an eyesore, could sprawl out in such an interesting way. I am hoping the audience will likewise reciprocate this emotional response, a response that I hope is only heighted by the greater ambition and scale of the rubbings and the newfound interconnectivity between them. It seems like there is a whole aspect of architectural space that is unexplored and ignored, which is the surface of buildings. I am interested in this idea of the “skin of the world”, capturing the minutiae of lived experience, of obsolescence and decline. This idea is something I share with Heidi Bucher’s work (see contexts). Her “Skinnings”, which are latex and textiles coated onto various architectural spaces, explore this in detail. Her presentation, choice of subject and deeply thoughtful motivations are an influence on my thinking going forward.

As a consequence of this continued fascination with cracks, I decided to do more research about them. Cracks are a form of zigzag, a pattern that holds an important place in our visual perception and is intrinsic to our anatomy (Barker et al., 2020). Human beings have always had a fascination with zigzags, with artists from precivilization all the way up to modernity being fascinated by all kinds of phenomena that share this pattern, including cracks. Doris Salcedo, an artist whose work I had become aware of earlier, I lately discovered also did work involving cracks (see contexts). Her work 'Shibboleth', plays on the idea of cracks acting like a schism, a metaphor of the broken system of geopolitics where inequality and racism cast a deep intractable trench that, although invisible, affects us all deeply. The power of cracks to create different narratives is interesting and I think very much applies to my own work.

My work touches on the studio, art institution and the arts in general, under threat and in a precarious position, something that the crack, as a visual device, suggestively points towards. In the wider context of my work the politics of an area, object and the associations it creates is interesting in terms of what I choose to rub, cast or print in some fashion in the future. This investigation of cracks is further developing my relationship with architectural space and how that is becoming a more important part of my work. It continues to act as memorial of my tactile journey in drawing, the experience of tactility transferring into an image. How that affects my audience and questions value and memory in the modern age continues to be key in my practice.

|

|---|

Crack Rubbing

The Initial idea was to do the sides below above as well as the ceiling. Unfortunately, I was not able to keep the ladder out long enough to attempt the ceiling and once term restarted it proved impossible to find the space and time. I did at least get to exhibit my work in a show in the summer at Spiral Galleries in Shoreditch (see professional skill section)

At around this time, I went to a series of shows that informed my thinking about materiality in my practice. The Wimbledon MA show that was delayed because of the pandemic was interesting to me. I thought about ways to manipulate paper and creating folds, from some of the work on show. The RCA show included some interesting works that were predicated on distressed surface, and this shaped my thinking about how my works, which are sculptural drawings might exist as they become more carved into by the graphite pencil. The Silver and metal MA final show at the RCA proved valuable, as I spoke to a recent graduate about the aesthetic of shininess, and he recommended a book that I found very illuminating. (See Relevant contexts).

References

Barker, G., Echevarria Aguirre, M., Berroya Elosua, A. & Morlesín Mellado, J. A. (2020).

THE SUMMER AT WILSON’S ROAD BUILDING

I was very excited about the prospect of working in the Wilson’s Road building. The former school is a grade II listed building and over 140 years old. I walked around the whole building, becoming a little overwhelmed by all the possibilities for various interventions in the space. I decided to treat the experience like a real residency, thinking about making the most of the historic space in the short time I had there.

|  |

|---|---|

|  |

|  |

|  |

Possible Projects

Parquet Floor

In the end I got very interested in scaling up the size of my rubbings and this led me to consider the architecture of the space itself. I wanted to get something that captured the spirit of the place, something emblematic of an institutional architectural space such as this one.

I felt the parquet floor best met my ambitions for creating a monumental work. There was also something just very beautiful about old floors that piqued my curiosity. The splashes and stains of art making, coupled with the ingrained surface of the wood being worn down and rubbed by the various imprints of humanity were something I wanted to get know better. I was also interested in thinking about space and turning my drawing more sculptural. I looked at different patterns, thinking about different ribbon shapes and how to fold paper. I came up with the idea of using the S-curve and created some sketches of how this might look in a space.

|

|---|

S-Curve Sketches in Architectural Space

|

|---|

Final Realisation of S-Curve Shape of Floor

I did this initially thinking about a curvature that would be dynamic and be an exciting shape that surprised the viewer, the eye passing up and down and then up again like the path of a rollercoaster. I then had the idea that the shape of the paper could be like the shape of the parquet floor pattern, the shape emulating its pattern. I later considered how this shape is going back to the idea of the zigzag shape that I had worked on earlier with cracks in the studio and perhaps coming something of a motif in my work. I then made more sketches, thinking about the actual measurements and positioning of the final piece.

|

|---|

Working Out Folding Measurements

Exact Measurements for the Rubbing

Furthermore, I was quite interested in Nancy Rubens work at this point. Her large paper graphite sculptures very ingeniously disrupted spaces by using less traditional parts of the gallery. I got very interested in the idea of using the corner of a room and creating a large sculpture that could take up less space. I did this firstly because I was interested with playing with the idea of using ‘void spaces’ in terms of the exhibition space. Places that don’t usually get used. This felt like it fitted into some of the ideas I was already thinking about in other areas of my work. Secondly, I was aware that Copeland had limited space and I was trying to think of ways to maximise the use of the space, while at the same time not disappointing my own ambitions for a very large rubbing work.

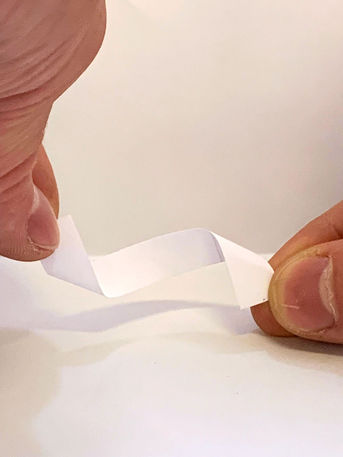

I then did some experiments with small strips of paper (1.100 ratio) to consider how the shape would look in the physical reality. It was at this point I probably should have made some bigger models, but more on that later.

Paper Folding Experiment

I made some test rubbings of the floor to decide how dark I wanted the larger piece to be. I also thought a lot about the gestural direction of the pencil on the wood to get the best rubbing. I decided on a mixture of downward strokes and a layer running along the grain of the wood to get some extra detail.

|  |

|---|---|

|  |

|  |

|  |

Successive Layers of Graphite on a Test Piece of Paper

I spent some time measuring and figuring out where the folds were to go in my work. I diligently discovered the right angles for folding the work, being careful not to lose the symmetry of the piece. I divided the rubbing into three parts: 1.9m, 2.8m and 1.9m, measuring when to turn the paper over for the three sections of rubbings. The middle would be on the other side while the two ends would be on the same side. I wanted to create a cylinder at the bottom of the paper rubbing, akin to an opened scroll. The idea was that it reminds the viewer of paper and the concept of conveying information by paper means, but also in a haptic way.

I decided on a mid-range tone that captured enough of the floorings patternation and the weathering it has received over the last century or so. This was also a pragmatic choice as trying to rub too many layers might have taken longer than the time allowed for the residency.

Sketchbook of Rubbing at Different Angles Against the Grain of the Wood; Parquet Floor Layer of Graphite

I Bought a 7m x 1.1m roll, carefully taping it down so that it fitted exactly within the area I wanted to rub. I then measured where the folds would need to take place.

|

|---|

Measuring Folds of the Paper Roll in Preperation for Rubbing

I began the rubbing, ensuring that it fitted exactly within the lines demarcated by masking tape on both sides, so it wouldn’t move while I made it. It took many hours, to bring to realisation.

Rubbing the Parquet Floor

Parquet Floor Various Stage

I also started to think more about the performative element of rubbing floors. I must make them, sitting, kneeling, almost bowed down in an obsequious pose. The act of getting closer to the ground, feeling the floor in an intimate tactile embrace, getting closer to it and its world, is part of the embodied experience of getting to know and love the surfaces and objects I choose to preserve through the act of rubbing. The performative act feels quite like Jessie Brennan’s Doormat rubbings which I discussed in Unit 2.

Parquet Floor Close Up

Stooped Over, Rubbing the Parquet Floor's Surface

Parquet Floor Rubbing Installation

Installing the rubbing in order to showcase it proved a distinct challenge and I learnt a great deal about working with very large paper from the experience. I planned how I might get the rubbing on the wall, in the end needing the help of five people. My initial thinking for the work was to use wire to hold the entire thing up. I still feel this might have been the best option as it would have allowed me to manipulate the shape of the paper better. However, I did not have a technical team to make this happen, so I decided to go with strong magnets. I measured and drew the space on the wall and then, with the advice of James Ireland, used string and nails to map out the shape of the rubbing on the wall. It helped me to also consider how far apart I ought to put up the nails which would hold up the magnets.

|  |

|---|---|

|

Sketchbook Notes for Installation

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

|  |  |

|

Installation Documentation

I was quite pleased with the overall outcome and eternally grateful to those who helped me with this tricky install. It ended up being quite difficult to get the exact fold of the shape I wanted. I underestimated how paper changes at larger scale and probably should have done some larger tests of how that would work. Speaking later to mujeeb during the group crit in term four, I think there is a great deal of power in taking large expanses of space and representing them in a different setting in this way and it is something I wish to make the mainstay of my practice in the future. He argued very, persuasively, that I was perhaps doing too much with my practice, overthinking things and trying to do too much. A simpler presentation might be a better option that doesn’t obfuscate from the experience of looking and appreciating them as they are.

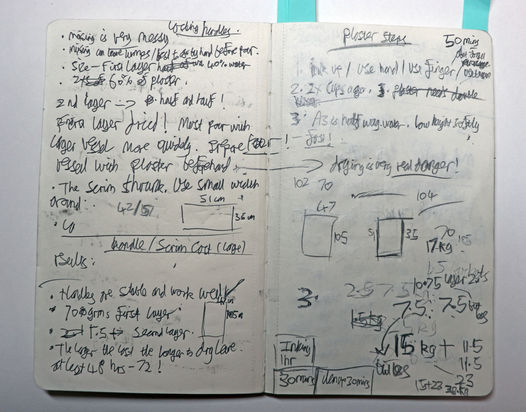

Experiments with Ink Plaster Casting

I was dividing my time between the parquet floor rubbing and concentrating on further experiments with plaster. I was still in two minds about the effectiveness of jesmonite as I had struggled to get it to work in the past. I thought it would be worth trying to experiment a little further with both plaster and plaster polymer and see which kind of cast I wished to make. I won’t talk at length about the many ways in which I adapted, learnt and improved the whole process of ink casting: How I learnt to finally get the right consistency; how it has to be thicker and hold less water to avoid losing detail; how I learnt to work larger and the difficulties with working with greater ratios that I had to overcome; how I learnt to use a plaster drill paddle effectively; how I experimented with adding handles to the back of the casts; how I considered the best way to spread the plaster over the inked surface; how I overcame air bubbles by banging the mixture before application; and how to apply scrim without using any pressure to strengthen the cast without causing imprints on the surfaces. I learnt a great deal of things to hone my skills during this period for the greater task ahead of casting in this difficult and inconsistent method at scale.

Successful Plaster with Scrim; Handle Experiments

Inking Up the Print Table Top

I found it interesting that I had to devise a new kind of way of inking the surface. I had to use my thumb, my little finger and even my fingertips to stroke the edges of the platform. I started to consider whether it would be possible to ink up the surface of the plaster that had gone white using my fingers. This is something I had discussed with Pete Roberts earlier. It might be something I develop further in the future. In a similar vein to the parquet floor there is also a performative act in touching and wiping these plates from the ground. Getting closer to their level, kneeling and bowing, inspecting them, caressing them and rubbing new life into them. This idea in unit 2 of the love object, of the dedication and ordeal of making them as well as sharing that emotional and physical engagement with the audience, like the floor, is still pregnant with meaning in both works. I wish to think more about performance elements in my work, much like Heidi Bucher does when she engages with surfaces, I want to instil that greater meaning in my future works.

Ink Casting with Jesmonite

I found that the jesmonite, finally, when applied properly and with the benefit of newfound adeptness of the process, can become successful ink casts as well. Although jesmonite is more complex and must be applied in thinner layers this is easier for the process. The mixture is much thicker than water-based plaster and these suites the process better. Its weight would be considerably smaller than plaster and it would potentially allow for larger casts that are at a safe weight.

Notes on Plaster; Successful Ink Jesmonite Cast

It looks more like a drawing, having a feeling akin to charcoal, with a moody and exceptionally delicate surface. It is more incomplete than plaster. The lines weave in and out of the viewers vision, with different parts producing a multi-layerered effect; much perhaps like the passing of time and the layered history that it is being printed from it. Its surface area is more susceptible to damage during the process, with flaking's and streaks of whiteness, bespattering and covering up the drawn lines in part. This made me think of the idea of memory, the traces of time that has gone by with each successive layer of marking making. How that it entwined with the history of the surface and how that becomes more inconsistent, distressed and ephemeral. My hope for future works is that it will act like a printmakers chronicle; a sensitive testament to the space, encapsulated through a collaborative attritional drawing.

I was influenced at this stage by the artist Tomas Saraceno, who I read about in Systems (2015) by Edward Shanken in Unit 1 (Shanken, 2015); The artist created a work called 14 billions (working title), in which he created a 3-D scan of a spider web, talking about the organic traces of nature. His work is always the subject of lively reinterpretation talking about different systems and how they might intersect across multiple disciplines. This made me think more about my own discipline of drawing, sculpture and print.

14 Billions (Working Title)

His work has been described in the following fashion:

“Each thread of silk marks an arc of movement: where the spider’s first aerial threads are forays into an imagined future, and the tensioned threads of the assembled web mark the axes along which the spider has already travelled. The spider/web is thus a living trace of movements and temporalities in tension: past, present and future (Editor, 2022).”

I found this description of the spider’s web very poignant for thinking about my own work. It made me reconsider the idea of the ‘meshwork’, which is discussed in Making (2013) by Tim Ingold. Ingold touches on the idea of the lines of a meshwork, being like a movement or growth (Ingold, 2013). He then goes on to discuss how drawing and lines can also be like an ongoing movement. The idea that lines can be haptic, inspired by ongoing movement, the organic embodied signature of lived existence, in this case that of creative endeavor is perhaps very important for the work. Like the spider's web it has its own living traces of the activities of human beings involved in printmaking. There is a kind of defiance, a transgressive quality to showing a meshwork of organic forming lines. It stands in stark contrast to the non-tactile, efficient, digitalized world of networks and straight lines that dominant our world.

References

Editor, W. (2022). 2-Dimensional Webs Archive/Maps and Traces STUDIO TOMAS SARACENO. STUDIO TOMAS SARACENO. Retrieved Oct 30, 2022, from

Ingold, T. (2013). Making (1. publ. ed.). Routledge. 10.4324/9780203559055

Shanken, E. A. (2015). Systems (1. publ. ed.). MIT Press.

AUTUMN TERM AND THE ROAD TO COPELAND

The autumn term was a time of intense experimentation even at this late stage. My primary consideration was how printmaking and rubbing/imprinting intersect with my practice. I really wanted to make use of the print room, which had been such a fertile ground of inspiration and discovery, while I still had access. I have a perpetual excitement when I come into that space, and it feels like a mania of invention whenever I go there.

Printing The Printing Press: The Bed of the Press

I continued to think about deconstructing the printing presses in the print room. Previously I had used rubbings to press the printing machine. I was still fascinated by this idea of the printing press almost experiencing itself and acknowledging its function by the act of making prints of itself. I thought about new ways to take imprints from the print room, considering taking an ink cast from the bed of the one of the broader Rochat printing press, or even inking it up itself.

|  |

|---|

Rochat Bed of the Press

After consulting the technician, we thought about how to apply ink to the bed of the press safely without damaging the blankets.

|  |

|---|

Bed of the Press Area Demarcated with Tape

I taped up an area that I found most alluring; a great deal of it having some very interesting surface marks from corrosion. I wanted to capture these traces of wear and tear, revealing the rich history of the surface that lies dormant beneath it. The ink revealed the grooves of the metal, demonstrating the fine grain of the surface. It's really quite a beautiful thing once you highlight it, which is exactly the aim of my practice, to make people look again at the beauty of the world through a haptic experience.

I took the unconventional step of removing the watermarks of the paper in order to get a complete uninterrupted print of the press.

Prints with Black Ink

Firstly, I made it in black and white, enjoying the feeling of the surface and getting to know it through the print making process. Not satisfied with the original print I took; I was influenced by Degas and the way in which he would use an extra piece of paper if he ran out of room when he used to do life drawings. I was lucky enough to see this in action when I saw his work at the Pompidou in France. I then proceeded to do a version in graphite powder. I want to imbue the print with some of properties of graphite, perhaps even some of its shine and reflectivity that are common with my rubbings.

Prints with Graphite Ink

The inherent raw tactility and beauty that has been discovered in these works, hopes to provoke questions about perception and what we value and appreciate in the world around us. I wanted my audience to draw the same conclusion that I did, which was ‘who would have thought this heavy slab of steel could be such a gorgeous feast to the eyes!’ I was researching into the work of Jennifer Bornstein and Heidi Butcher at this time, and they were proving revelatory in terms of thinking about the emotional content of my work, the ephemeral, loss and the sublime.

At around this time I saw the drawing reflections lecture for ‘Lines of empathy’, by Giulia Ricci. I was very interested in the idea of cognitive embodiment, in which it is posited that there is a close connection between our body function and our cognitive function. We perceive things in a certain way that informs how we see the world based holistically on our bodies. In the modern age we are losing that ability to physically relate to each other, a way to understand the way the body is speaking to us about ourselves and about the world. The body has huge knowledge that relates to the physical act of perceiving and recording what is in our environment. I find it interesting that this is suggestive of an unconscious autobiographical content to the way we might make art, especially in my case that is based so much on haptic embodiment. Cognitive embodiment, and the act of making art that intersects with this, helps one to find themselves and make oneself a fuller, richer human being.

I then had a tutorial with Giulia Ricci, about my practice that proved quite informative. She suggested I try to experiment with colour in some form, pointing out that colour helps give a sense of physical presence that might be absent in monochrome drawing. She encouraged me to question how I can make the material show off its properties in the best way. She likewise suggested that I might think about making rubbings outside, something I have also considered, having looked at the nature imprints of Yves Klein and the work of Raquel Serrano during my extended research. I am quite interested in trying to contact the local council and get access to rub old telephone boxes, and perhaps other printmaking experiments. The weather is always the biggest concern when making rubbings outside that has been somewhat of a deterrent thus far. She encouraged me to look at the works of the Portuguese artist Diogo Pimentão, whose work I saw at Patrick Heide gallery in the spring, as well as the Monograph (2021) of Rana Begum. From Begum I was very inspired by the way in which she hangs her work in space and this has given me ideas. Finally, she mentioned the catalogue of touch at the Fitzwilliam Museum last year in 2021, which has proved extremely informative.

Ink Cast of The Etching Room Floor

Following on from this, I took an ink cast of the ink stains on the etching room floor. I thought about what would best typify the ink markings, considering an area that would really capture something of the vivacity of these gestural ink blots, informed in part by the earlier rubbings I had made in Unit 2. Exploring surfaces that are ultimately walked on and ignored, the leftovers from the process of etching, but have so much vitality and beauty as rubbed marks, was of key concern in starting this project. I re-examined my research into Ingrid Calame's work in unit 1, as well as the casting practices of Rachel Whiteread. Unlike Calame, I was interested in exploring drawing and printmaking rather than painting, but like her and Whiteread, we all share an innate desire to champion the abject and void space that carry a rich seam of human activity and presence.

Ink Stains on the Floor Selected for Ink Cast

I proceeded to rub ink into the floor, however it didn’t work out as expected, the ink failing to adhere to the surface as I would have hoped.

White Ink Cast

I remembered that Pete Robert’s had suggested I try rubbing back into the cast with ink to eliminate white spots, so I did this for the floor cast. I practiced on some old, used casts with various scrim; however even cheese cloth came out with a brownish colour that I felt didn’t have the right colour or consistency to succeed for the purpose of reconstituting ink into the lines. I tried using just my finger and vigorously wiped any excess ink on the back of scrim and tissue paper to create a very thin layer of ink on my finger for the purpose.

Rubbed Ink Cast

It came out better this time, creating a blacker, clearer effect. I found using my hand allowed me to almost touch and feel the cast back into life, giving it animus through repeated rubbing with my fingertips. I then found out I could also use a rubber to remove tone if necessary. This feels like quite an exciting realm of possibility in terms of creating a vocabulary of marks for ink casts in the future.

Frottage and Sculpture: the Etching Room Floor

I started taking rubbings on tracing paper and choreographing the ink stains on the print room floor. The premise being that I would I then use these tracings to consider the best frottage, rendered on bible paper in graphite. In a similar way to my ink cast of the print room floor, I was looking at Ingrid Calame’s work at this time. I did this because I wanted to create a more sculptural haptic experience of the print room. I turned back to the work of Jane Eaton and iza Genzken’s, who I discussed in unit 2, thinking about producing sculptural prints of frottages using screen etch resists. I was also very keen to produce an object that could be touched, bringing my audience closer to the haptic encounter I was hoping to share with them. This would take the form of the etching plate itself, the idea being to buy the biggest plate possible to etch (in this case 60 x 50 cm), then bend it into a cylinder. I would then present the sculptural print and the plate next to each other as a final outcome – an outcome that expresses my interested in the expanded field of printmaking and drawing.

I have always found etching plates to be incredibly intricate and pleasing things in themselves, having thought that I would love to do something more with them. I am looking at my own tools and, in a way, making artworks about the materials and processes of etching itself; the experience of etching, now in even more physical forms.

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

|  |

Choreographing Ink Stains Through Sight and Touch

I spent a long time looking at marks that I thought were beautiful, almost looking at them as if they were characters. I then rubbed them in order to see how they would look in a frottage composition and I found a lot of marks that looked particularly abject were in fact some of the most beautiful.

Rubbings on Tracing Paper

I then conducted a test on zinc using random marks in soft ground in order to check the viability of bending an etched plate. I etched the marks for exceedingly long time, almost to the point that the ground ripped off from the metal. I then tested the cylindrical sculpture in metal and found that it worked rather well. It was at this point I knew I was going to lose studio access soon and there was an onus to focus down sharply on the work for Copeland. I therefore put all my energy into the works I had set out in the exhibition proposal, following the advice from Sarah during my tutorial.

Etched for 40 Minutes, ¼ Nitric, Bent on Sheet Metal Machine

I then conducted a test on zinc using random marks in soft ground in order to check the viability of bending an etched plate. I etched the marks for exceedingly long time, almost to the point that the ground ripped off from the metal. I then tested the cylindrical sculpture in metal and found that it worked rather well. It was at this point I knew I was going to lose studio access soon and there was an onus to focus down sharply on the work for Copeland. I therefore put all my energy into the works I had set out in the exhibition proposal, following the advice from Sarah during my tutorial.

SCALING UP THE INK CASTS

I created an ink cast in plaster partly as a test run to see how this process would work at a larger scale. Partly just for my own personal satisfaction and curiosity to see the difference between Jesmonite and plaster.

Mixing Plaster

Large Plaster Cast

It turned out well formed although unclear and lacking in detail. It was also very heavy. This confirmed to me the need to persevere with jesmonite. I proceeded to figure out how to cast jesmonite at scale, playing with the ratio until I discovered that about a 2:1 ratio of plaster to jesmonite worked best.

Notebook Calculations and Polymer; Ratio to Create a Jesmonite Ink Plaster Cast

I then used the project space as a casting room and methodically inked up the different sections and cast them in turn over the course of two weeks.

Inking the table top; the Inked Surface After Casting

All Four Ink Casts

The larger casts came out well, their newfound materiality and scale worthy of further consideration. As I mentioned in Unit 2, these casts act as a kind of print of a drawing of the life of human activity. They are a testament to the activity of printmaking and a collaborative drawing by a multitude of printmakers over many years. I found the fragile and ephemeral nature of these casts were only further highlighted at larger scale. Plaster is a delicate material by nature, often regarded as transitory and impermanent. Much like the marks that it has revealed, its materiality provides a certain preciousness, transience and delicacy. This quality can be well exemplified by the plaster works of Maria Bartuszová, whose casts at the Tate Modern, shows just how sensitive plaster can become (producing thin and incredibly delicate renderings of egg-like sculptures). This coupling of the intricacies of delicate surfaces revealed by ink combined with this quality in plaster adds to the beautiful reinterpretation of lived experience. I also found it interesting that the increased weight and scale of the casts was in stark contrasts to the tiny and the intricate that the process revealed (I also found it important to think how a score mark could be considered a crack, just at a much smaller scale, suggesting more linkage between my works). The cast’s inherent fragility and the delicate subject matter again add to this idea of unearthing something delicate and precious.

The ghostly drawn lines revealed on the surface of the ink opens a window into a different universe of textural subtlety, the jesmonite capturing many tonal ranges and questioning what's there in front of us. It highlights the predominance of vision to simplify and ignore the intricate and the beautiful in what lies just below the surface of things. I feel it bridges the gap between sculpture, print and drawing, it is like a more physical version of a large rubbing, subtle yet substantial, delicate but solid. It further blurs the line between what sculpture, drawing and printmaking are and possibly what they could be.

At around this point I had a few tutorials that proved quite helpful in thinking about my practice. Paul Coldwell talked to me about the idea of my rubbings 'mirroring the world' and that by rendering reality slightly differently I was touching on the uncanny, which is something I wish to research further. He also talked to me about the importance doing something really difficult and ambitious with my rubbings in particular.

The group crit with Mujeeb was very important for the future direction of my practice. From this I gathered that the larger rubbing works are more successful; making large scale rubbings should be the mainstay of my practice. The tutor thought that focusing down very finely on one process was the best course for success for my art practice. Despite Mujeeb's imprecations to avoid focusing on more than one thing for maximum success, I cannot entirely turn my back on printmaking and other experimentations. I will attempt to have printmaking or other ideas in the background as a more silent partner.

SHATTERED

I began to take a rubbing of a shattered window in the studio storeroom. My original concept for the work was to turn the rubbing into a screen etch resist and explore different printmaking options. I began by first thinking about how to attach the bible paper onto the window surface, measuring the near exact proportions of the window and then after a period of trial and error, moulded the paper to the appropriate shape. I placed tape around the edges of the frame, carefully rubbing the surface of the paper with my hand until it created a tight seal, reducing the chance of air pockets as well as getting the paper as close as possible to the surface being rubbed.

All Four Ink Casts Rubbing the Window; Sketchbook Rubbing Plan; Moulded Paper and Various Pencil Lengths for Different Areas

Shattered First Draft

After the first draft I made a rubbing plan which utilised multiple gestural pencil marks based upon how I could fit my hand into the space without compromising on the smooth consistent application of graphite. The whole process took on a distinctly sculptural character: I was burnishing the paper and moulding it with my fingers, getting my nails into the edges. The act of moulding required the paper to be folded, wrapped, pushed, pulled and stretched to its limit in order to get the smallest membrane between the pencil mark and the paper. Once the rubbing began, I used several sizes of pencil, which acted almost like carving tools, each being used with precision to avoid tearing the paper excessively and get into small nooks and crannies. I took the rubbing from its first tentative layers all the way to the point where I felt it could get no darker.

Shattered: Different Graphite Layers

My original concept for the work was to go as far as the paper surface would possibly allow. The slow act of rubbing the surface to a shine with graphite, and the buckling surface under pressure from a multitude of successive layers, is like a perverse reversal of the quick process that caused the shattering to begin with. The word ‘shattered’ means to be tired or worn down, it is a signifier of defencelessness, vulnerability and 'disruption’ in the community (Castello di Rivoli, n.d.). It is an obsolete thing that talks about decay. I have ironically reversed this and turned a broken window into a fetishized love object. All that attention and labour has turned this drawing sculptural; it has literally become carved into the space through successive layers of graphite.

Shattered Graphite Rubbings: Light, Medium and Dark

At this point I had a tutorial with Sarah, in which she suggested I try to take a screen print of the rubbing and look at the works of Marcel Duchamp (see contexts) and Jasper Johns. In each the artists are challenging their audience to consider whether their work is an object or a painting, a print or a sculpture, blurring the lines between different forms. John’s Flag (1954) is both the representation of an object but also could be considered that object itself. This same notion is also true of my work, in that my rubbings are a highly detailed, sculptural print of the surface rubbed. For johns the work was not so much about what was being represented but in the process of transforming something “common to everyone and doing something with it” (www.people.vcu.edu, n.d.). In a similar way to my work, Flag suggests the uncanny representation of things focused on the process of making and giving people pause for thought.

I turned these into screen prints, playing around with inking as well as toning with different coloured papers.

Shattered Screen Print Evolutions

I did this in preparation for printing it on glass and aluminium, further blurring the lines between whether it is a sculpture, a print or a drawing. I printed it on aluminium as well as on glass because I wanted to think about removing it slightly further from its original context. I also put it in a free-standing frame for the same purpose and to make it more of an object. I was interested in Jasper John’s flag and Duchamp’s Fresh Widow (1920) (See Contexts). Like Duchamp’s leather, I have ‘shined a window’, but in this case it is broken playing with the politics of space and the idea of the studio, I am shining what is broken, highlighting but also trying to restore what is fractured. The idea of studio as a broken thing is intentional, but it is a greater reflection on not just exploring architecture and the politics of space. Like the crack works, it is another example of the interesting tension that the juxtaposition of subject matter and materiality inherent in rubbings can pose to the viewer. It offers an uncanny experience and from that encourages reappraisal about what they think they know about perception, representation and the identity and soul of different spaces.

References

Castello di Rivoli. (n.d.). Hito Steyerl. The City of Broken Windows. [online] Available at: https://www.castellodirivoli.org/en/mostra/hito-steyerl-the-city-of-broken-windows/.

In-text citation: (Castello di Rivoli, n.d.)

www.people.vcu.edu. (n.d.). Jasper Johns. [online] Available at: http://www.people.vcu.edu/~djbromle/modern-art/02/jasper-johns/index.htm.

© 2022 By Tom Harper